*Poniżej angielskiej wersji tego wpisu znajduje się wersja polska.

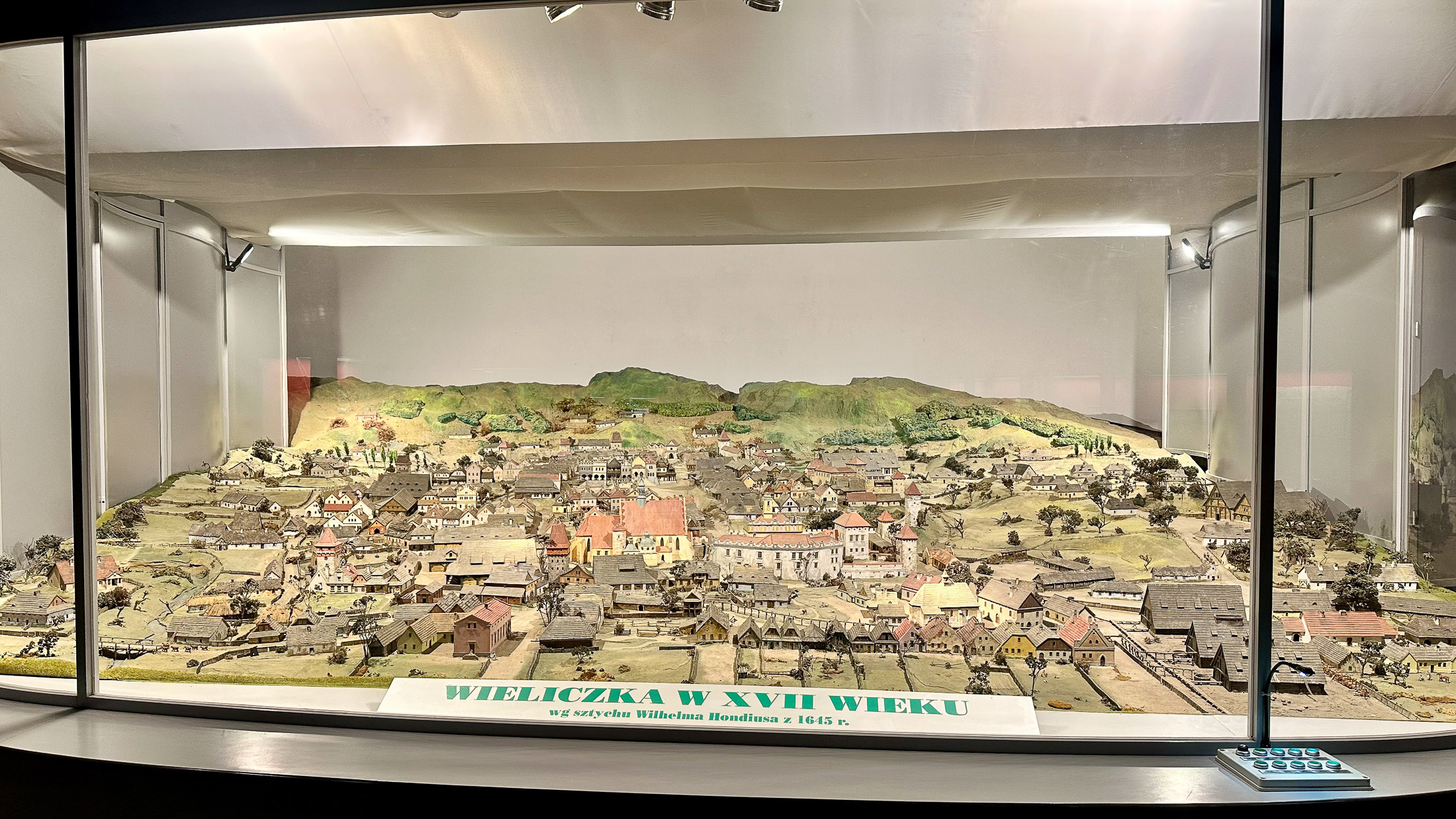

The Wieliczka Salt Mine, located just outside Kraków, is one of Poland’s most famous historic landmarks and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. First opened in the 13th century, it produced table salt for nearly 700 years, making it one of the world’s oldest continuously operating salt mines until commercial mining ended in 1996. The mine stretches through more than 287 km (about 178 miles) of underground tunnels and reaches a maximum depth of 327 meters (1,073 feet)—roughly the height of the John Hancock Center in Chicago—though only a small fraction is open to visitors.

The mine is divided into two main sections: the Tourist Route and the Museum Route. The Tourist Route covers the first three levels and takes about 1.5 hours to walk the 3.5-kilometre (2.2-mile) trail. Highlights include the famous St. Kinga Chapel, intricate interior designs carved in salt, and brine lakes—one of which hosts a sound and light show featuring the music of Frédéric Chopin. After completing the Tourist Route, visitors can continue to the Museum Route, located entirely on the mine’s third level. This 1.5-kilometre (0.9-mile) trail takes around 50 minutes and features Europe’s unique collection of horse mills, salt crystal exhibitions, and monumental chambers such as the Maria Teresa and Saurau Chambers. With its underground lakes, intricate salt carvings, and centuries of history, the Wieliczka Salt Mine offers a remarkable glimpse into Poland’s industrial and cultural heritage.

Over its long history, the mine has drawn many notable figures. Among its visitors are Nicolaus Copernicus, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Fryderyk Chopin, Dmitri Mendeleyev, Ignacy Paderewski, Robert Baden-Powell, Karol Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II), and U.S. President Bill Clinton—some names I recognized instantly and others I honestly didn’t. Either way, the list shows just how significant the mine has been across generations.

My aunt Gosia drove in from Grajewo to visit us for a few days, her first time ever in Tarnów. Her visit lined up perfectly with a long weekend for the boys, who had Monday and Tuesday off from school, so one of the things we planned was a trip to the Wieliczka Salt Mine near Kraków. On one of her last days with us, we made the short drive out to Wieliczka. It was a gloomy, overcast day, so spending a few hours underground sounded better than being above ground anyway. We parked a short walk from the mine, bought our tickets for the 2:05 p.m. tour, and still had about half an hour to grab snacks while we waited. Tours seemed to run every 5–10 minutes, which was incredible considering how many people were visiting—especially since it was Poland’s Independence Day, a national holiday. Groups of 40–50 people were the norm, and the flow of tours heading into the mine felt endless.

After grabbing some fries from a restaurant near the entrance, we picked up our tour headphones and headed inside, descending countless flights of wooden stairs. I lost track after about ten minutes, and by then we were already deep underground. Our guide mentioned that the deepest point of our route would be around 135 meters (443 feet)—roughly the height of a 40-story building. Whenever we entered a sealed chamber, one door had to close before the next could open to prevent strong drafts from rushing through the mine. Slowly, we worked our way through a maze of tunnels and chambers as the guide shared the mine’s long history. The mine is enormous—our hour-and-a-half tour covered only a tiny fraction of what lies beneath the surface. The kids did great the entire tour, walking for hours with no complaints, which made the experience even more enjoyable for all of us.

At the end of the tour, we emerged into an underground gift shop. From there we could either head back up or continue into the additional Museum Route, which was included in the ticket. Of course, we explored the museum too—another set of long corridors filled with artifacts and displays before finally taking the elevator back up to ground level.

Wersja po Polsku:

Kopalnia Soli Wieliczka, położona tuż pod Krakowem, jest jednym z najsłynniejszych zabytków w Polsce i znajduje się na liście światowego dziedzictwa UNESCO. Pierwsze wydobycie soli rozpoczęto tu w XIII wieku, a kopalnia produkowała sól spożywczą przez niemal 700 lat, czyniąc ją jedną z najstarszych nieprzerwanie działających kopalni soli na świecie, aż do zakończenia komercyjnego wydobycia w 1996 roku. Kopalnia rozciąga się na ponad 287 km (ok. 178 mil) podziemnych tuneli i sięga maksymalnej głębokości 327 metrów (1 073 stopy) — mniej więcej tyle, co wysokość John Hancock Center w Chicago — choć tylko niewielka część jest dostępna dla zwiedzających.

Kopalnia podzielona jest na dwie główne trasy: Trasę Turystyczną i Trasę Muzealną. Trasa Turystyczna obejmuje pierwsze trzy poziomy i wymaga około 1,5 godziny, aby pokonać 3,5 km (2,2 mile) ścieżki. Najważniejsze atrakcje to słynna Kaplica św. Kingi, misternie rzeźbione wnętrza z soli oraz solankowe jeziora — jedno z nich służy jako scena dla pokazu dźwięku i światła przy muzyce Fryderyka Chopina. Po zakończeniu Trasy Turystycznej zwiedzający mogą kontynuować Trasę Muzealną, znajdującą się w całości na trzecim poziomie kopalni. Ta 1,5 km (0,9 mile) trasa zajmuje około 50 minut i obejmuje unikalną w Europie kolekcję młynów konnych, ekspozycję kryształów soli oraz monumentalne komory, takie jak Komora Marii Teresy i Komora Saurau. Dzięki podziemnym jeziorom, misternym rzeźbom solnym i wiekom historii, Kopalnia Soli Wieliczka oferuje niezwykły wgląd w polskie dziedzictwo przemysłowe i kulturowe.

Na przestrzeni wieków kopalnia przyciągnęła wielu znanych gości. Wśród odwiedzających byli Mikołaj Kopernik, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Fryderyk Chopin, Dmitrij Mendelejew, Ignacy Paderewski, Robert Baden-Powell, Karol Wojtyła (późniejszy papież Jan Paweł II) i prezydent USA Bill Clinton — niektóre nazwiska od razu rozpoznałem, inne szczerze mówiąc nie. Tak czy inaczej, lista pokazuje, jak ważna była kopalnia na przestrzeni pokoleń.

Moja ciocia Gosia przyjechała z Grajewa, aby spędzić u nas kilka dni — po raz pierwszy w Tarnowie. Jej wizyta przypadła idealnie na długi weekend dla chłopców, którzy mieli wolne w poniedziałek i wtorek, więc jednym z naszych planów była wycieczka do Kopalni Soli Wieliczka pod Krakowem. W jeden z ostatnich dni jej pobytu wybraliśmy się na krótką przejażdżkę do Wieliczki. Pogoda była ponura i pochmurna, więc kilka godzin spędzonych pod ziemią brzmiało lepiej niż przebywanie na świeżym powietrzu. Zaparkowaliśmy krótki spacer od kopalni, kupiliśmy bilety na wycieczkę o 14:05 i mieliśmy jeszcze około pół godziny na przekąski, czekając na rozpoczęcie. Wycieczki odbywały się co 5–10 minut, co było niesamowite, biorąc pod uwagę liczbę odwiedzających — szczególnie że tego dnia obchodzono w Polsce Święto Niepodległości. Grupy liczyły zwykle 40–50 osób, a napływ turystów do kopalni wydawał się nie mieć końca.

Po zjedzeniu frytek w restauracji przy wejściu odebraliśmy słuchawki i ruszyliśmy do środka, schodząc niezliczone drewniane schody. Straciłem rachubę po około dziesięciu minutach, a w tym momencie byliśmy już głęboko pod ziemią. Przewodnik wspomniał, że najniższy punkt naszej trasy sięga około 135 metrów (443 stopy) — mniej więcej tyle, co 40-piętrowy budynek. Za każdym razem, gdy wchodziliśmy do zamkniętej komory, jedno drzwi musiały się zamknąć, zanim otworzono kolejne, aby zapobiec gwałtownym podmuchom w kopalni. Powoli przemierzaliśmy labirynt tuneli i komór, słuchając historii kopalni. Kopalnia jest ogromna — nasza półtoragodzinna wycieczka obejmowała zaledwie mały ułamek tego, co kryje się pod powierzchnią. Chłopcy spisali się niesamowicie podczas całej wycieczki, przechodząc godziny bez żadnych skarg, co uczyniło doświadczenie jeszcze przyjemniejszym dla nas wszystkich.

Na końcu trasy wyszliśmy do podziemnego sklepu z pamiątkami. Stamtąd mogliśmy albo udać się na powierzchnię, albo kontynuować Trasą Muzealną, która była wliczona w cenę biletu. Oczywiście zwiedziliśmy również muzeum — kolejne korytarze wypełnione eksponatami i wystawami — zanim w końcu wjechaliśmy windą na powierzchnię.

To było fascynujące doświadczenie od początku do końca i naprawdę jedno z tych miejsc, które pokazuje, ile historii może kryć się pod naszymi stopami. Powinniśmy byli odwiedzić je dużo wcześniej, gdybyśmy wiedzieli, jak niesamowite jest.

Methane gas, which is lighter than air, would accumulate in the upper parts of the mine, creating a serious explosion risk. To prevent disaster, experienced miners—often crawling through narrow tunnels while wearing wet clothes—used long poles tipped with burning torches to ignite the gas. This critical safety measure was extremely hazardous, making it the most dangerous job in the mine.

Horses were an essential part of the Wieliczka Salt Mine’s operations, serving as the powerhouse behind much of the underground work. They walked in treadmills and powered windlasses to lift salt to the surface, hauled loads through the tunnels, and assisted with other vital support tasks. Trained to work in the dark and confined spaces, these horses often spent their entire lives underground. Remarkably, the last horse left the mine as recently as 2002, reflecting how long this traditional system persisted.

St. Kinga's Chapel, located 101 meters (331 feet) below ground and rising 11 meters (36 feet) high, is a vast space carved entirely from salt. It is adorned with elegant chandeliers and numerous works of art, including a stunning altar several hundred years old, also made completely from salt. Today, the chapel continues to host church services, concerts, and even weddings.

The Warszawa Chamber is used for balls, banquets, parties, conferences, symposiums, trainings, concerts, theatrical performances, anniversaries, integration events, and other special occasions.

Once the official tour ended, we continued on to the Museum Route.

It was a fascinating experience from start to finish, and truly one of those places that shows just how much history can be hidden beneath your feet. We would have visited much sooner if we knew how incredible it would be.